Bisley, El Yunque (Caribbean) National Forest

Bisley #3 Stream

Monday, November 7, 2016

Monday, January 2, 2012

Friday, April 18, 2008

Monday, April 9, 2007

Sometimes this is what you get!

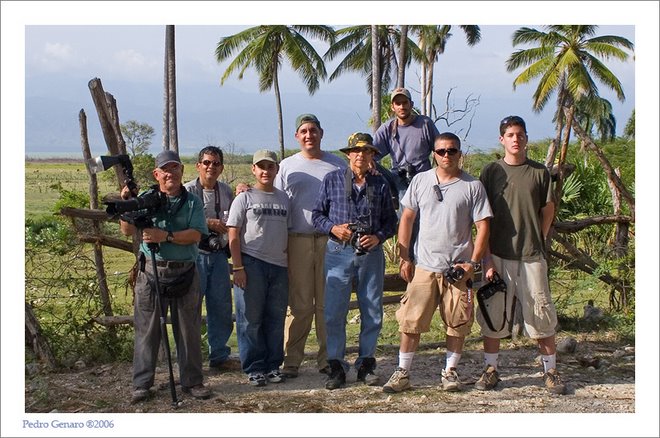

In many instances, people ask how we are able to take photos so close to the different organisms we photograph. You could use "blinds" to hide, use camouflage and walk slowly, just get a lucky break, or other methods. But, sometimes you'll get what you deserve for taking risks while trying to capture "the image". For example, I have been stung by scorpions, stung by a swarm of bees, wasps and even almost had my head shaved by the claws of a female Accipiter striatus (Halcón de Sierra; Sharp-shinned Hawk).

During this photo session, after taking approximately 65 photos, ironically on the last photo and for no apparent reason, the bees attacked. Unluckily for me, 14 bees (that was the count of stings on my face) got inside the face mask I was wearing and stung me. The only thing I could do was walk away from the nest as calm as I could. After looking for any reason for the attack, we agreed that they were probably provoked by the dark camouflage jacket I was wearing.

The photo that follows shows how close I was to the beehive and was taken right when the attack started. The photographer (Arq. José G. Baralt), even though he was wearing a protective mask he had to rush out of the area to avoid being also stung.

In another case, to photograph this Pandion haliaetus (Aguila Pescadora; Osprey) at the Piñones State Forest,

To take this photo of a Chordeiles gundlachii (Querequequé; Antillean Nighthawk) that was nesting at the El Tuque area in Ponce, Puerto Rico,

I had to crawl about 150 feet!!! (Photo Below)

Friday, April 6, 2007

Are you into butterflies?

Anartia jatrophae - very common on mangrove and wetland areas.

Archaeoprepona demophoon ramosorum - these guys feed on tree sap.

Archaeoprepona demophoon ramosorum - these guys feed on tree sap.

Some of my "stinging foes".

Would you like to find these guys while walking at night inside a forest... it is better than the "Chupacabras"? ¡Ja! Well this comes with the territory; it is either this or just passing by a Urera baccifera or Ortiga Brava in your face.

Polistes americana

Tityus obtusus

Puerto Rican Screech-Owl

One night after searching for Eleutherodactylus populations at the El Yunque National Forest (formely known as Caribbean National Forest), while driving down on PR-191, this guy was perched on the left side of the road. It is the endemic Puerto Rican Screech-Owl (Megascops nudipes). This is a nocturnal species very common in forested or wooded areas.

Coquí Guajón

This is Eleutherodactylus cooki, the second largest species in Puerto Rico and locally known as Guajón or Coquí Guajón. It is considered an endangered species because of its habitat requirements and its extremely limited geographical distribution. This species is restricted to the southeast region of Puerto Rico and found in areas around the towns of San Lorenzo, Patillas, Maunabo, Humacao, Yabucoa, Juncos and Las Piedras. It is found at low and intermediate elevations (36 to 360 meters) in areas locally known as "Guajonales"; which are caves and/or large crevices formed by large basalt-granite boulder assemblages, usually adjacent to streams or flowing water. This species exhibits sexual dimorphism in vocalization, size and coloration. The males are yellowish from the tip of the lower mandible to the abdomen and flanks, while the females are white.

Top view

Male

Female

Coquí Llanero

In an island that is approximately just 100 x 35 miles, is was a surprise that last year a new species of Eleutherodactylus was discovered by Dr. Neftalí Ríos now at the University of Puerto Rico-Humacao. The new species was found in a small wetland area located at the abandoned U.S. Navy Base of Sabana Seca. Already the area is under pressure by development. This is the smallest Eleutherodactylus found in Puerto Rico, and is related to another species found at the island's mountain peaks, Eleutherodactylus gryllus. I won't include photos of the plant which serves as the habitat for obvious reasons.

Thursday, November 30, 2006

Tarantulas: Amazing Spiders

Tarantulas are considered by many people as dangerous animals. They even have been used by the motion picture industry as instruments of terror in films, such as the science fiction horror film, Tarantula (1955). Even in the first agent 007 film, Dr. No (1962)where one scares the hells out of James Bond, and in, Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Arc (1981), among many others. In Indiana Jones, they used close to 100 live tarantulas.

Tarantulas are considered by many people as dangerous animals. They even have been used by the motion picture industry as instruments of terror in films, such as the science fiction horror film, Tarantula (1955). Even in the first agent 007 film, Dr. No (1962)where one scares the hells out of James Bond, and in, Indiana Jones: Raiders of the Lost Arc (1981), among many others. In Indiana Jones, they used close to 100 live tarantulas.

In spite of their menacing appearance, many tarantulas are actually docile toward humans, and only attack in self-defense when it raises its hind legs and shows its shiny black fangs (chelicerae), as shown on the photo of Phormictopus cancerides, above on the left.

Tarantulas are large hairy spiders with approximately 1,500 species in the world. There are some 30 species in the United States and 7 species in Puerto Rico.

The largest living arachnids are both the Goliath  tarantula, Theraphosa blondi, and its sister, Theraphosa apophysis, both from South America. Pseudotherathosa apophysis is the biggest tarantula, with a leg span of about 13 inches (33 cm). These arachnids have a very long life span; some species can live over 30 years. Phormictopus cancerides, a tarantula from the Hispaniola, has been identified as the largest tarantula of the Antilles with 16-18 cm (both photos on the right).

tarantula, Theraphosa blondi, and its sister, Theraphosa apophysis, both from South America. Pseudotherathosa apophysis is the biggest tarantula, with a leg span of about 13 inches (33 cm). These arachnids have a very long life span; some species can live over 30 years. Phormictopus cancerides, a tarantula from the Hispaniola, has been identified as the largest tarantula of the Antilles with 16-18 cm (both photos on the right).

tarantula, Theraphosa blondi, and its sister, Theraphosa apophysis, both from South America. Pseudotherathosa apophysis is the biggest tarantula, with a leg span of about 13 inches (33 cm). These arachnids have a very long life span; some species can live over 30 years. Phormictopus cancerides, a tarantula from the Hispaniola, has been identified as the largest tarantula of the Antilles with 16-18 cm (both photos on the right).

tarantula, Theraphosa blondi, and its sister, Theraphosa apophysis, both from South America. Pseudotherathosa apophysis is the biggest tarantula, with a leg span of about 13 inches (33 cm). These arachnids have a very long life span; some species can live over 30 years. Phormictopus cancerides, a tarantula from the Hispaniola, has been identified as the largest tarantula of the Antilles with 16-18 cm (both photos on the right). Because of their weight, they can't spin webs, so each species either lives in underground burrows, on the ground, or in trees. Tarantulas eat insects, other arachnids, small amphibians and reptiles, bird chicks and mice.

Because of their weight, they can't spin webs, so each species either lives in underground burrows, on the ground, or in trees. Tarantulas eat insects, other arachnids, small amphibians and reptiles, bird chicks and mice.

In reality, tarantulas have simple eyes (photo on the right) and can only distinguish between light and darkness, and since they are nocturnal, they find their way by the use of sensitive hairs on their legs and bodies. In fact, they can sense your approach just by detecting the vibrations caused by your moving feet.

Somewhat at odds with their fearsome appearance, tarantulas as well as all spiders are fastidiously clean animals. Especially after eating, they will spend long periods of time rubbing their legs together and over their bodies in order to clean off any remains of the prey and other debris.

Although they have the ability to jump up to a few inches, they possess sticky hairs on each leg which allows them to climb almost anywhere. Depending on the species they can be found on the ground or in trees, where they line their burrows with silk.

All tarantulas drinks extra water before molting and does not eat for one week. Like typical spiders, tarantulas produce silk, but is variously used to line their lairs, create egg-sacks, and in the case of trap-door spiders, to form a hinge for the earthen door to their burrows.

In Puerto Rico, there are seven species, among them the terrestrial Cyrtopholis portoricae (photo on the left) and the arboreal Trichopelma corozae and Avicularia laeta. Despite their ferocious appearance, no one has ever died of a tarantula bite. Because of their weight, they can't spin webs; so depending on the species,they either live in underground burrows, on the ground, or in trees.

In Puerto Rico, there are seven species, among them the terrestrial Cyrtopholis portoricae (photo on the left) and the arboreal Trichopelma corozae and Avicularia laeta. Despite their ferocious appearance, no one has ever died of a tarantula bite. Because of their weight, they can't spin webs; so depending on the species,they either live in underground burrows, on the ground, or in trees. The Puerto Rican Pygmy, Cyrtopholis portoricae is the most common species of tarantula in Puerto Rico. Although it is called a "pygmy", they are medium-sized terrestrial tarantulas that live in burrows digged on the ground, where they can be found during the day. This species has a dark brown with light rosy stripes on each leg. Some people regard them as extremely aggressive, this is exagerated. They will defend themselves if provoked or if they feel threathened.

The Puerto Rican Pygmy, Cyrtopholis portoricae is the most common species of tarantula in Puerto Rico. Although it is called a "pygmy", they are medium-sized terrestrial tarantulas that live in burrows digged on the ground, where they can be found during the day. This species has a dark brown with light rosy stripes on each leg. Some people regard them as extremely aggressive, this is exagerated. They will defend themselves if provoked or if they feel threathened.Another uncommon species is the arboreal, Trichopelma corozali an endemic species which

also has the ability to climb; during the day they dwell in burrows excavated on tree trunks or among the roots. As you can see on the photo on the left, these hideouts and the entrance are covered with silk. The second

photo was taken on the trail to Mt. Britton at the El Yunque National Forest (formely known as the Caribbean National Forest) after the spider emerged from its burrow during the night. It can be easily identified by just looking at the abdomen with dark-grey or black hairs.

photo was taken on the trail to Mt. Britton at the El Yunque National Forest (formely known as the Caribbean National Forest) after the spider emerged from its burrow during the night. It can be easily identified by just looking at the abdomen with dark-grey or black hairs. Avicularia laeta, or the Puerto Rican Tree Tarantula, is also an endemic species to the Greater Puerto Rican Region. Unlike other tarantulas, this species is adapted to an arboreal lifestyle, because they possess under the distal portion of the legs made of

Avicularia laeta, or the Puerto Rican Tree Tarantula, is also an endemic species to the Greater Puerto Rican Region. Unlike other tarantulas, this species is adapted to an arboreal lifestyle, because they possess under the distal portion of the legs made of microscopic hooks; this allows

microscopic hooks; this allowsthem to walk over branches and leaves. It builds silk nests in holes in tree-trunks or in the crevices of large boulders and at limestone cliffs. They can also build their nests in the central rosettes of some species of bromeliads, as you can observe on the photo on the right. This photo was taken at St. John, U.S.V.I; the first two were taken at the University of Puerto Rico, Humacao.

Pepsis vs Holothele

One the most remarkable natural events, is the relationship between the wasp, Pepsis ruficornis (first photo at the end) and the tarantula, Holothele sp. The female wasp actively looks for a tarantula; when one is found, she stings the tarantula, and then with her antennae determines if is the right species. The wasp next digs a hole where she will bury the spider and then lays one egg next to it. After it hatches, the larvae will be nourished by slowly eating the spider, keeping it alive by saving the vital organs for last. In the last two photos you can observe the wasp in pursuit and when it tries to sting the small tarantula. The outcome... the predator not always win.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

729.jpg)

773.jpg)

760.jpg)

.JPG)

.JPG)